A Not Quite Elegy And Also Some of My Favorite Poems

The first (and only) fight I ever had with my college girlfriend was over poetry.

It is the one thing I still think about and mull over when I think about her and our relationship. Her vehement dislike for the art form still baffles and saddens me. I showed her a poem that I found online and has since been tragically lost to time. It was posted by a poetry professor and was written by his mother who has suffering from an extended battle with Alzheimer’s. He had given her a task that he also gave to his students: write a poem where each line began with “I am…” “I see…” “I wish…” etc. It was an exercise focused on the senses. What are you experiencing and how does that experience translate into poetry? What emerged from this woman was a moving and visceral portrait about the end of your life and what it feels like to slowly lose your memories. One of the final lines of the poem was about how the writer wants to be back in the room where they play chess again. The poster revealed that the “they” in question was his parents, and his father had died some years before.

How beautiful. How sad. How lovely.

I wish I remembered the exact lines, or even the name of the professor who posted it. All I remember was what I felt when I read it. I was overcome with such profound grief and love for someone I will never meet. I wanted her to be reunited with her husband in the room where they play chess, as bittersweet as that reunion would be.

I wanted to share this poem with my girlfriend, naturally. I wanted to share everything that I found beautiful in the world with her. Just like how I remember my reaction, I remember hers too. She was angry.

Angry.

At what? I am still unsure. I tried to get her to explain and all she could say was, “it’s sad. It was written to be sad.” To which I responded, “It was written by a woman with Alzheimer’s, of course it’s going to be sad.” More words were exchanged, and I continued to be confused about why this poem that I found to represent all of the wonderful and heartbreaking things in the world could produce such ire in someone I also thought was all of the beautiful and good things in the world.

We ended the fight in resignation on both of our ends. She agreed to not bring this up again, and I agreed to no longer share poetry with her.

Looking back on it, I’m still saddened by the idea that she is unable to see the beauty in poetry. I hope since then she has found a poem or two that she likes.

When I was nine years old I put together a poetry anthology.

The anthology, entitled “Something Must Be Missing” was a collection of all of my favorite poems. I made the book myself with a manilla folder as a cover and printer paper on the inside. I bound the book with some thick string and decorated the cover with scrapbook paper I had lying around.

Inside the book I painstakingly copied down every single one of my favorite poems. I don’t know how remarkable it is for a nine-year-old to have a favorite poem, much less enough to fill an entire volume (slim as it was). But by the time I was nine, I had many favorite poems, some long and rambling like Lewis Carroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter” and some short and simple like “This Is Just To Say” by William Carlos Williams. I loved all of them, with an intense and pointed focus I only directed at my very favorite things. For years the collection sat on my bookshelf next to Shell Silverstein and Dr. Suess.

I remember always loving poetry. Some of the first books that I owned were Where The Sidewalk Ends and The Dream Keeper. Shoutout to my parents for thinking that a five-year-old who has just learned to read should have poetry included in their expanding library. I have an early memory of being read a poem that included the line “flip my pillow over to the cool side,” and understanding that feeling and thus understanding what the poem was about. The relatability of that line unlocked something in me that festered into a lifelong love affair.

My first tattoo was an homage to Wendy Cope’s The Orange;” and I memorize and recite poems to combat panic attacks. The poetry unit in my HL English class (the equivalent of AP Lang and Lit in the International Baccalaureate program) was my favorite because it gave me tools to understand how poetry worked on a structural and alchemical level. So, when my book club picked a collection of Mary Oliver poems for our book that month, I was ecstatic, only to discover they were not as interested in breaking down the structure of “Wild Geese” as I was. (No shade to my book club, if they are reading this. I loved that discussion regardless). I still write down poems that I find, just like how I did when I was a child. On a recent trip to New York, I saw a poem posted on the subway and I took a picture of it and immediately wrote it down once I was off the busy train. What a treat, I thought, to be gifted with the beauty of human emotion on a busy train car.

I think that’s my favorite part of poetry – the emotion. Poetry is the best way to tap into the soul of humanity. It is designed to make you feel. Something, anything. I think of the line in Dead Poets Society (Weir 1989) where John Keating (Robin Williams) is impressing on his students why they need to love poetry. He says:

“We don't read and write poetry because it's cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for. To quote from Whitman, "O me! O life!... of the questions of these recurring; of the endless trains of the faithless... of cities filled with the foolish; what good amid these, O me, O life?" Answer. That you are here - that life exists, and identity; that the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. That the powerful play *goes on* and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?”

He quotes Walt Whitman’s “O Me! O Life!” a poem about the simplicity and yet beauty of humanity. A personal favorite of mine. Perhaps that scene from the Dead Poets Society is overplayed at this point, but I always rewatch it and think “yeah, he’s got it.” This is why we are alive. We are alive for poetry.

I compiled some of my favorite poems and some words about why I like them below. I hope you are able to find some new ones that you like too.

The last time I checked, my college girlfriend was still subscribed to this newsletter, despite us breaking up over a year ago. Maybe she’ll enjoy some of them too.

“The Orange” by Wendy Cope

At lunchtime I bought a huge orange— The size of it made us all laugh. I peeled it and shared it with Robert and Dave— They got quarters and I had a half. And that orange, it made me so happy, As ordinary things often do Just lately. The shopping. A walk in the park. This is peace and contentment. It’s new. The rest of the day was quite easy. I did all the jobs on my list And enjoyed them and had some time over. I love you. I’m glad I exist.

I like to think of this poem as my poem. This orange is my orange. That selfish idea is because of my tattoo inspired by the poem which rests on my forearm in a way where whenever I can always see it whether my arms are resting by my side or they are in motion.

“I love you. I’m glad I exist.” It’s such a simple and small idea, and this poem is about simplicity and small joy in life, “As ordinary things often do/Just lately.” I love the tranquility of this poem — I love finding the small joys in my own life.

“I love you.” The you is imperative here. It is the first time in the poem, the speaker directs the story outward. The “you” could mean someone that the speaker is talking to — the person they are talking to about the huge orange, or it could be to the reader. I love you, the person reading this. I like to think that it’s both.

“Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carroll

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand;

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree

And stood awhile in thought.

And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.This is one of those aforementioned poems I memorized to stave off panic attacks. I have always loved the rhythm of it, especially when spoken aloud. It almost demands to be performed, which is why it is a helpful recitation tool when my mind is panicking.

I love Carroll’s use of nonsense words. In that first stanza, Carroll intermixes real words like “tove,” “gyre,” and “gimble” with his own creations: “brilling, ”“mimsy,” “outgrabe,” “borogoves,” and “mome raths." The latter two are animals that Carroll made up: apparently a borogove is a mop-like bird, and a rath is a kind of green pig. “Mome,” is another Carroll-word, potentially meaning “from home,” so a “mome rath” is a lost rath.

This brings us to the two most important creations of the poem: the titular Jabberwock and the frumious bandersnatch. The Jabberwock is traditionally depicted as a dragon, or a septent adjacent creature. Carroll scholars are unclear about what a bandersnatch could look like. In Carroll’s epic poem “The Hunting of the Snark” the bandersnatch reappears with a long extendable neck. I like to imagine the bandersnatch as mammalian beast, similar to the Catbus in My Neighbor Totoro.

The serpentine Jabberwock is also appealing to me, specifically because of how it goes along with the serpentine structure of the poem. Carroll’s stanzas have uneven indentations, giving each line a wavy structure. Much like the toves, the poem is also slithy (meaning lithe and slimy).

“A Glimpse” by Walt Whitman

Whitman is one of my favorite poets. Not really a bold or radical take, he is considered one of the great American masters. I love a great deal of his poems, “I Sing the Body Electric,” “I Saw in Louisiana a Live-Oak Growing” and the aformentioned “O Me! O Life!” are other favorites. But I knew I needed to include this one when I sat down to write this piece. This was in part because it was my first exposure to Whitman’s work. But really it was because of how I came to this poem.

In high school, I was sitting in class when I received an email from my then girlfriend (also in class). The subject line read, “This made me think of you,” the body contained a link to this poem.

“Of a youth who loves me and whom I love, silently approaching and seating/himself near, and that he may hold me by the hand.”

I felt nice to be loved like that.

“Planet of Love” by Richard Siken

Richard Siken and Walt Whitman are tied together in my mind, despite being two very dissimilar poets. It’s probably the fact that they are both gay (although most of the poets featured here are as well) and probably because I came across both of them at relatively the same time. Both poets are also adept at writing longing and desire in a way that hits me at my very core.

“Planet of Love” from Siken’s monumental collection Crush is devastating. While not his most explicit, or emotional, or painful, it is the one that sticks with me the most. I love how Siken uses Hollywood and the falsehoods of cinema to represent lost love. Who is responsible for the death at the center of the poem? Is it the speaker, who’s the director in the helicopter? Or is it “you,” this enigma that “everyone’s watching eveyone’s/curious, everyone’s/holding their breath.” in anticipation for? Or maybe it is the circumstances themselves that created this tragedy.

I love how Siken uses punctuation and structure in his work — particularly here, both with the repetition of “Imagine this:” and all of the intentional periods. Periods that are representing the ends of thoughts but will be broken up into three different lines. He adds double meanings in his structure. There is one thought represented by where each sentence begins and ends and another where each line break happens.

[Buffalo Bill’s] by E.E. Cummings

“[Buffalo Bill’s]” is probably my favorite poem. It’s my current lock screen on my phone, and a poem that lingers in my brain all the time. I could break it down line by line, and talk about Cumming’s use of free verse, his open structure, the rhythm, particularly with the line “and break onetwothreefourfive pigeonsjustlikethat”. But instead this is a poem where I want to focus on the feelings, which I don’t know how to articulate, but I certainly feel something when I look at it.

I’ve spoken before about how I like art that sticks. I like to think about what remains. I’m struck by many things in this one. The brackets around the title, “defunct,” on it’s own line, “Jesus” on its own line, followed by “he was a handsome man,” and the last thought Cummings leaves us with: “how do you like your blue-eyed boy/Mister Death.”

“Fungi” by Collette Bryce

I told myself I would limit this piece to just one Irish poet, so I went with Bryce. “Fungi” comes from her collection The M Pages, which is an elegy about Bryce’s sister, the titular M, whose death prompted the collection. “Fungi” is the last poem in the collection before Bryce shifts to writing about M and writing about her grief.

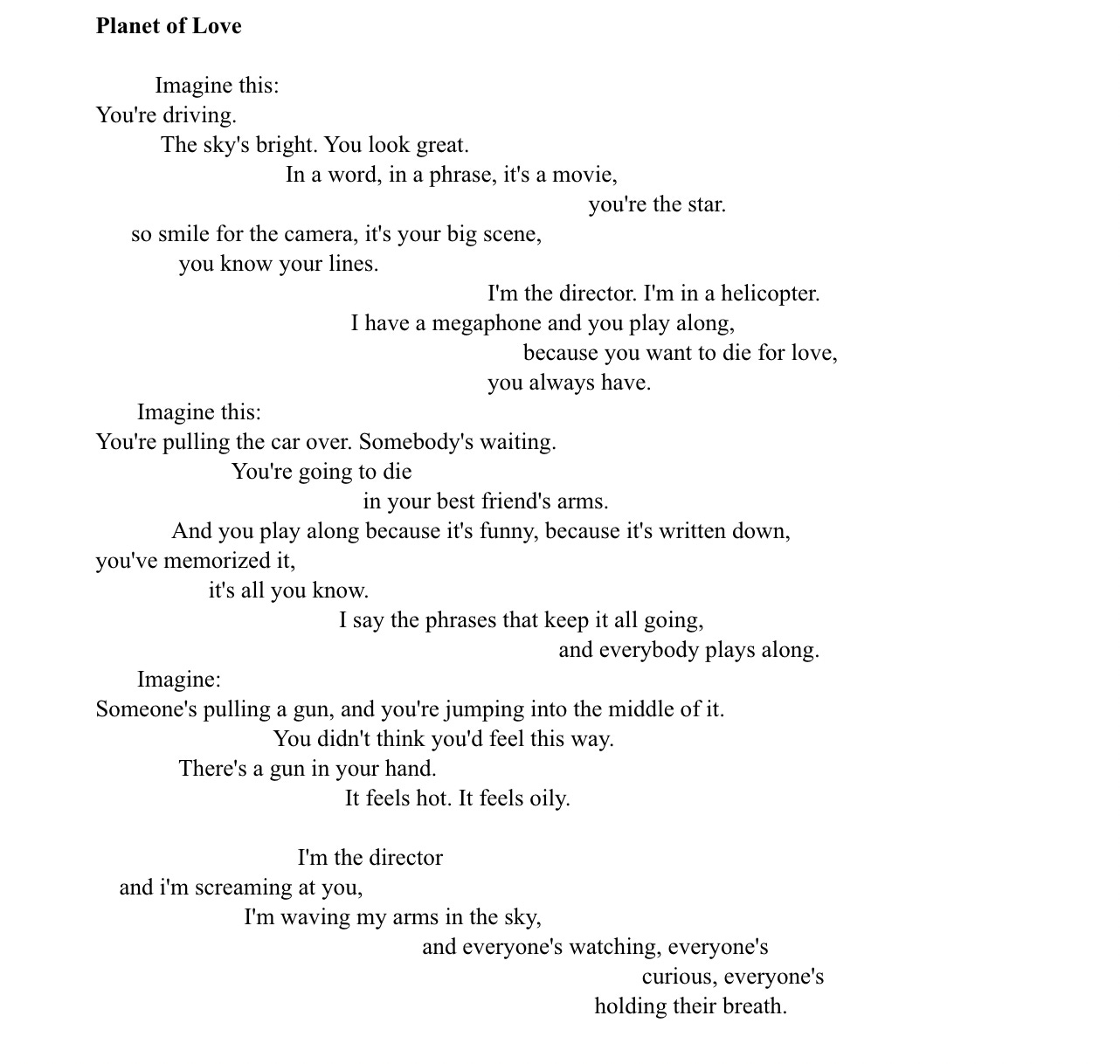

It is my favorite from the collection because it is the one that made me feel the most. In the photo above, you can see my annotations. Unlike the other poems, which I dissected with such intensity you can barely read the poems, this one made me so sad the only thing I could add was a drawing of a pear and a note that reads “I can’t do this one.”

I included this photo rather than transcribe the poem because I wanted you to see my annotations and also because I wanted to note how this poem is laid out in the book. The last stanza “who don’t/even realize/you’re dead.” is on a separate page. It is set apart from the body of the rest of the poem and therefore is a little more work for the reader to read. This gives it more of an impact and it slows down the flow of the poem. By putting the stanza on a separate page Bryce lets that it linger a little longer. It marks the shift in the rest of the collection and in the tone of the whole poem. It is no longer about something abstract, like the slow death of a poem, it is concrete now. It is about the death of one individual, who doesn’t even know that they are dead.

I hope you enjoy these poems. I enjoyed sharing them with you.