In my last semester of undergrad, I took a class about cinephilia. Cinephilia, using the Greek root "-philia,” meaning “to love,” is a kind of love of the movies. It is an unnatural love of movies and of movie culture more specifically. As my professor pointed out, everyone likes the movies, but you have to love the movies. The cinephile is not just someone who watches movies, they live for the movies. The cinephile is not just content with watching a movie for the plot, they watch the movie for everything about the movie. They are not content with just a story. As a classmate of mine said, “if I wanted to tell stories, I’d be a novelist. I want to make movies.”

Part of the cinephile is the ritual of the movies. For my part, I have to sit in row M in the third or fourth seat from the right. I am far enough back, I can see the exits, and I do not have to crane my neck. I must have popcorn. I will arrive ten to fifteen minutes early so that I can see all of the preshow extras. To go to the movies — to watch a movie at all — is a religious experience for the cinephile. At least, it is a religious one for me.

Part of this discussion of cinephilia was a discussion of the canon. The cinematic canon are the films heralded as the best of the best. The most important films ever made. These are the films that are in the top ten lists and on every single college syllabus. Every ten years, the prestigious Sight and Sound Magazine and British Film Institute collect a ballot of the top ten films of all time from critics, filmmakers, programmers, curators, academics, and archivists. They compile the lists together to find the 250 definitive greatest films ever made. If you’ve ever heard someone say that Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) is the greatest film ever made, it is because of the Sight and Sound magazine. In 2012, Kane was dethroned by Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), and in 2022, Vertigo was unseated by Chantal Ackerman’s slow cinema masterwork, Jeanne Dieleman, 23 Quai du Commence, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). (For what it’s worth, Vertigo was number two and Kane was number 3).

The thing about the canon is, it is incredibly subjective. Much like most things in this world, it is dictated by the loudest voice in the room. It is dictated by who has the most power. That means that a lot of times the canon is reflective of one single perspective and this perspective is usually white and male. Only rarely do new films get to come into the canon. In nearly every single college class I took, I watched Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989). If I hadn’t taken a class specifically about Spike’s films, I doubt I would have seen any other film of his for school. Do The Right Thing is in the canon. In the 2022 poll, it is ranked twenty-fourth. Spike Lee has been anointed.

The canon also tends to skew older. It is unfavorable to films from the 2010s or even from the 21st century at all. Notably, the 2022 poll drew some criticism for the new additions: Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Sciamma 2019), Moonlight (Jenkins 2017), Parasite (Bong 2019), Get Out (Peel 2017), Twin Peaks: The Return (Lynch 2017), Under the Skin (Glazer 2013), Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller 2015), Zama (Martel 2017), and Petit maman (Sciemma 2021). All of these films, despite coming from great masters like David Lynch and new auteurs like Bong Joon Ho and Jordan Peele, were cited as “too recent.” But really, when you look at those films, can you argue that they are not the best films of the last decade?

To return to the topic of cinephilia, I think it is important that the canon is subjective. As a critic, I am not concerned with the objective qualities of a film. I am much more concerned with the lasting impact of a movie and with how it makes me feel. What remains. I frequently talk about M. Night Shyamalan’s Old (2021) as an example of what compels me as a critic. Objectively, I think Old is a bad movie. However, I have thought about it at least once a week since I saw it three years ago. I bring it up to almost everyone I talk to. Old has remained. I wouldn’t place it into the canon, but I would place it as important. The great Susan Sontag once wrote of the movies,

…it was from a weekly visit to the cinema that you learned (or tried to learn) how to walk, to smoke, to kiss, to fight, to grieve. Movies gave you tips about how to be attractive…Even more than what you appropriated for yourself was the experience of surrender to, of being transported by what was on the screen. You wanted to be kidnapped by the movie -- and to be kidnapped was to be overwhelmed by the physical presence of the image.

Old kidnapped me. Simple enough.

As part of this class I took on cinephilia we had to assemble our film canon. We had to be specific about it, not just the movies that made us cinephiles, or the experiences that kidnapped us, but the exact moments. Not just Lost in Translation (Coppola 2003), as my professor shared, but the moment that Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) touches her pinky to Bob’s (Bill Murray). That small moment of shared intimacy. These moments had to be the first time and the most recent time, because, my professor told us, we fall in love with the movies every time we watch one. We are always finding these little moments. As the lights dim, we are kidnapped once again. As Nicole Kidman once said, “heartbreak feels good in a place like this…because here it’s real.”

Here are my moments.

George Banks walks away from the camera into the London matte painting as “Feed the Birds” plays, Mary Poppins (Stevenson, 1964).

Mary Poppins was one of my favorite movies growing up. I have strong childhood memories of faking illnesses so I could stay home and watch this movie on my parents’ portable DVD player. I had the soundtrack on CD and I would play it every night to fall asleep. I played Jane Banks in a youth production of the stage show. It was, and still is, so important to me.

This movie is full of great cinephilia, “How did they do that? “I can’t believe it” moments. But it’s this one. This is the one that gets me. That I get. Mary Poppins is a movie that is so vibrant and alive. It pulses with all of the energy of a big-budget movie musical. In the film, the contrast between “Step in Time” and this scene is almost jarring. The movie takes its time to come to almost a complete halt as George Banks (David Tomilson) prepares to lose his job. This stillness is notable. It is heavy.

As George Banks walks towards the bank, “Feed the Birds” — a song that once promised happiness in the simple actions of genuine human kindness — becomes a funeral march. Mr. Banks calmly accepts his fate. He is prepared to lose everything, even, as the scene before foretells, his job and his family. In doing so he would forfeit his place as patriarch, something he has fought hard to achieve. With Michael’s tuppence in hand, George is prepared to grovel at his boss’s feet. But on his walk, he pauses at St. Paul’s Cathedral to look for the bird woman, only to find her missing. Mr. Banks has made his choice, he has chosen his job, and as such given up on the simplistic and magical whimsey of Mary Poppins and his children.

But, once he is in the meeting, Banks is confronted with the superficiality of it all and the love of his children. Michael has given him the tuppence — a childish act of grace that he hopes will smooth the whole ordeal over. And it does. George realizes that his children love him and want him to love them. His job doesn’t matter. The tuppence doesn’t matter. His wife matters. His children matter. The rest is supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

It’s magical. It catches me off guard every time. This moment always pulls the whole movie into focus for me. It has never been about Jane and Michael. It has always been about George. It is about how he learns to be a father again. I love it.

Hugo hanging off the hand of the clock like Harold Lloyd in Safety Last!, Hugo (Scorsese 2011)

Martin Scorsese’s 2011 film Hugo is a love letter to silent cinema. Scorsese is part of the first generation of “Film School Brats.” Filmmakers who learned to make films in film school. But if you actually asked him, Scorsese would say that he learned to love movies — learned to be a cinephile — watching TV broadcasts of Powell and Pressburger films in his mother’s living room. Like most of us, he learned to love movies by watching movies.

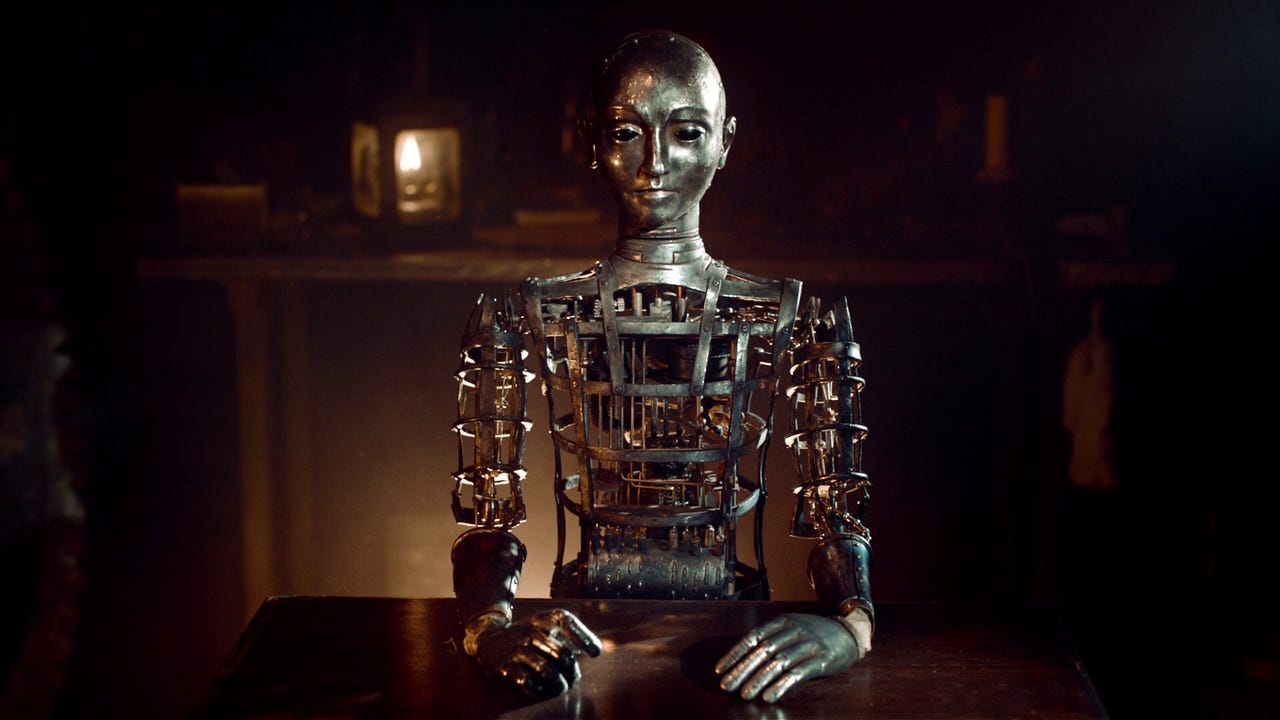

Unlike Scorsese, I learned to love movies by understanding them. As with most things I enjoy, I need to dissect it to love it. In order to love something, I have to take it apart and put it back together, like a video player, or an automaton.

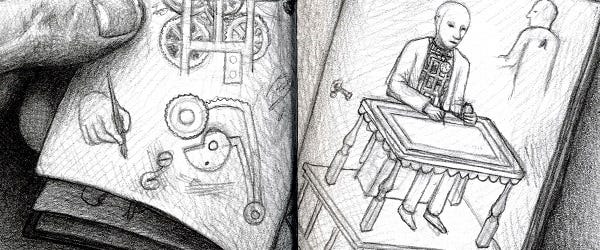

Hugo is based on the Brian Selznick “novel,” The Invention of Hugo Cabret. I use “novel” in quotations and exceedingly loosely because over half of the book is told in illustration. Selznick was an illustrator for children’s books before he became a writer, and his book was innovative in the way it wove together the story in image and in the written word. It was awarded the Caldecott Medal in 2008 — an award usually given to children’s picture books.

In addition to being a novelist, Brian Selznick is also the great-nephew of Hollywood icon, producer David O’Selznick. If that name doesn’t immediately ring a bell, Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, and A Star is Born, — all of which Selznick produced, might. Early Hollywood is quite literally in Brian Selznick’s blood.

Both the film and the novel follow the titular Hugo Cabret as he seeks to restore an automaton that used to belong to his father. Mysteriously the old toymaker at the train station where Hugo works and lives in has all the pieces to fix the automaton. It turns out this toy maker is famed silent filmmaker Georges Méliès. Hugo, along with some newfound friends restores Méliès’ spirit and restores the films.

Méliès was a real filmmaker (we’ll hear more about his work later) but the story is fictional. After World War I, his films were mostly destroyed and Méliès faded into obscurity. He is still fondly remembered by critics and academics for his contributions to cinema, but most people do not know his name the way they know Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin.

“Most people” does not include a seven-year-old kid in Denver, Colorado named Morgan Ward.

Because here’s the thing, even as a kid I was like this. I was a cinephile. I largely credit The Invention of Hugo Cabret for making me a cinephile. (Years later I would discover that my mentor at film school was the chief consultant on the book and it felt like my world had come full circle).

After reading this book a couple hundred times, I needed to watch silent films. I was lucky enough to have a public and school librarian who encouraged this newfound obsession and set me up with a library computer where I could watch silent films online for free. I watched as much of Méliès’ work as I could. I watched Chaplin, Keaton, and Harold Lloyd.

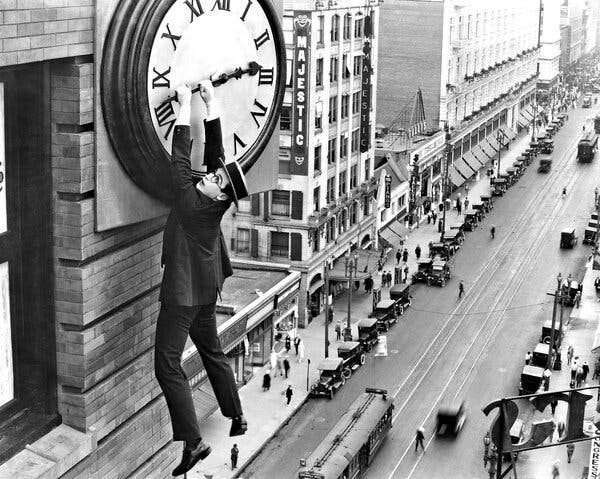

Which brings me to this scene in Hugo and precisely why it is the moment for me. Hugo hanging from the hand of the clock tower is a direct reference to Harold Lloyd doing the same thing in Safety Last! (Newmeyer and Taylor 1923).

Scorsese knows this. It is intentional. The image of Harold Lloyd hanging from the clock tower (which was a real stunt he did), is one of the most iconic images in American cinema. Hugo is filled with little references like this. This image was the poster for the movie. It is hardly remarkable. But to me, the now nine-year-old who needed to dissect everything they saw in order to love it? This was movie magic. Because I could look at that scene and say “That’s a reference to when Harold Lloyd did the same thing in Safety Last! I know this reference!” I suddenly realized that movies were full of references. And the more movies I watched, the more references I would understand. Watching Hugo hang from the clock hand, I unlocked all of cinema.

The astronauts leave the rocket and walk on the moon, Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon) (Méliès 1902)

I said we would arrive at Méliès, and we did. The technical, historical, and academic aspects of this film aside, there is something so wondrous about this movie — even one hundred years later. It is what my dreams look like. The way Méliès captures surrealism and fantasy in this film is still untouched to this day.

The image of the rocket shooting directly into the eye of the moon is iconic. It is referenced in countless other films. Even if you haven’t seen this film, you know this image. But what was, and still is, more amazing to me, is watching the astronauts emerge out of the rocket. Somehow — perhaps it is the already dreamlike cinematography, Méliès’ revolutionary editing, the impeccable production design, or all of the above — it looks and feels real. I gasp every time the astronauts emerge and set foot on the moon. There they are! They made it to the moon!

I have always lived in a world where people have been to the moon. I know what’s there. I know that people have walked on it. But Méliès, who died thirty years before man set foot on the moon, had to imagine what the moon must be like. He was the old astronomer, knowing nothing with any certainty, but knowing that the sights of the stars make him dream.

If he is the astronomer, then I am his pupil. When those astronauts emerge, it is like something out of my wildest dreams. This is what film was made for. Méliès was the first person to get it. It was for documenting dreams. This is what dreams look like. Men on the moon.

Le voyage dans le lune is available in HD on YouTube. If you’ve never seen it, you should try dreaming sometime.

The wide shot as Cinderella and her prince begin to dance and the world falls away, Cinderella (Jackson et al 1950)

Cinderella (1950) is the only animated film on this list, which surprised me as I sat down to compile it. Animation has had a huge influence on me as a cinephile and as an academic. My undergraduate thesis work was written on three works of animation. There are moments of animation that have had profound impacts on me. But none of those moments left the same impression that this moment does. They don’t have the “lean in” quality. The Sontag kidnapping.

This moment is similar to others on the list. I’m drawn to beautiful colors, orchestrations, and dance. But what sets it apart from other animated moments and from the other live-action scenes is, much like Le voyage dans le lune, the dreamlike quality of the sequence. Everything about this moment is hazy and faded. As the rest of the world falls away, you feel caught up in the thrill of first love. As Cinderella hums, “ ah, so this is love.” Love is dancing. It is the moment someone sees you across a room and you see them and everything else falls away. It is picturesque, it is beautiful. In “The Decay of Cinema,” Sontag says that movies taught us how to fall in love, and what love looks like. We learned what love was from the movies. I learned what love was watching this scene.

On his podcast, Blank Check with Griffin and David, actor Griffin Newman talked about how what set the first thirty years of Disney animation apart from the rest was the lack of screenplay. These films were compiled in storyboards, with the animators deciding what story beats they wanted to hit and what was the most visually appealing. It is why in Sleeping Beauty (Geronimi 1959) there’s an extended sequence where the fairy godmothers change the colors of Aurora’s dress back and forth. It is visually interesting. This moment in Cinderella is needed for the plot – Cinderella and her prince have to meet – but the beauty of it is that it exists just to look beautiful. It is beautiful because the point was elegance and beauty.

This moment doesn’t translate outside of animation either. When Kenneth Branagh adapted the 1950 film to live-action in 2015, he attempted to restage the same scene. The effect is lost. It is no longer dreamlike and hazy. Instead, the frame is overstuffed and gaudy. It is impossible to achieve the same quality of desire and love because the intention of the scene has shifted. Branagh’s goal is no longer, “What looks beautiful?” It has become, “How can I recreate this scene?” The simple answer is, “You can’t.” You can’t fall in love for the first time again. You can fall in love again, sure. But that first love, the first time you danced, the first time you discovered it and watched the world fall away, that cannot be recreated. It is unique and special.

George Bailey begs Mr. Potter for the money to save the building and loan and Potter refuses, knowing that George’s money is in his desk drawer, It’s a Wonderful Life (Capra 1946)

If Cinderella taught me how to love, then this scene taught me how to grieve.

I would like to think that as children we all think that the world is good and that most people are good. We haven’t experienced evil yet. Most of us haven’t. I would hope.

This is the scene where I first understood that there were people in this world who were evil. Evil isn’t reserved for fantasy and horror. Real people can be evil, without any depth to them.

It’s a Wonderful Life (Capra 1946) is an exercise in watching the worst things happen to the best guy you know. George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart) is designed to be the everyman. He is you and he is your best friend.

I think most people remember this movie just for act three – where after George almost attempts suicide, his guardian angel presents him with a world where he was never born; he sees the impact he had on the world, and he asks to live again. If this film isn’t part of your yearly holiday rotation, you might forget that in the first two acts of the film we watch George Bailey’s life play out in full. From stopping the accidental murder of a little girl at the hand of a grieving druggist, through marriage, fatherhood, and saving his father’s business. At every turn, we are watching George Bailey’s dreams crumble out from under him, and the ways that a new one is erected. We see how he picks himself up.

He wants to go to college, but right out of high school, he cannot afford it. So, after working for two years with his father at the Bailey Building and Loan, he has saved up enough money. But, the night he is scheduled to leave, his father has a heart attack and dies. So, he gives the money to his younger brother, with the agreement that when Harry returns, George will get to go to school. But when Harry comes back, George discovers that he’s married, and his new father-in-law has offered Harry a job ten times better than the building and loan. So, George stays in Bedford Falls, and his dreams of college and European travel are abandoned. But then he marries Mary Hatch (Donna Reed) and it looks like the young couple will get to travel the world together. Except, it’s October of 1929, and share prices on the New York Stock Exchange have plummeted. George Bailey runs a building and loan company; he doesn’t have money. But the people need money and without hesitating the new Mrs. Bailey asks, “How much do you need?” and offers up the honeymoon money.

Over and over again he loses and rebuilds.

At every turn, George is about to be outsmarted by Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), who owns every building in Bedford Falls, except for the Bailey Building and Loan. He can’t buy out the company and he can’t buy out George. George Bailey is smarter than that, better than that. He scrapes by the skin of his teeth, but he can do it.

Until he can’t.

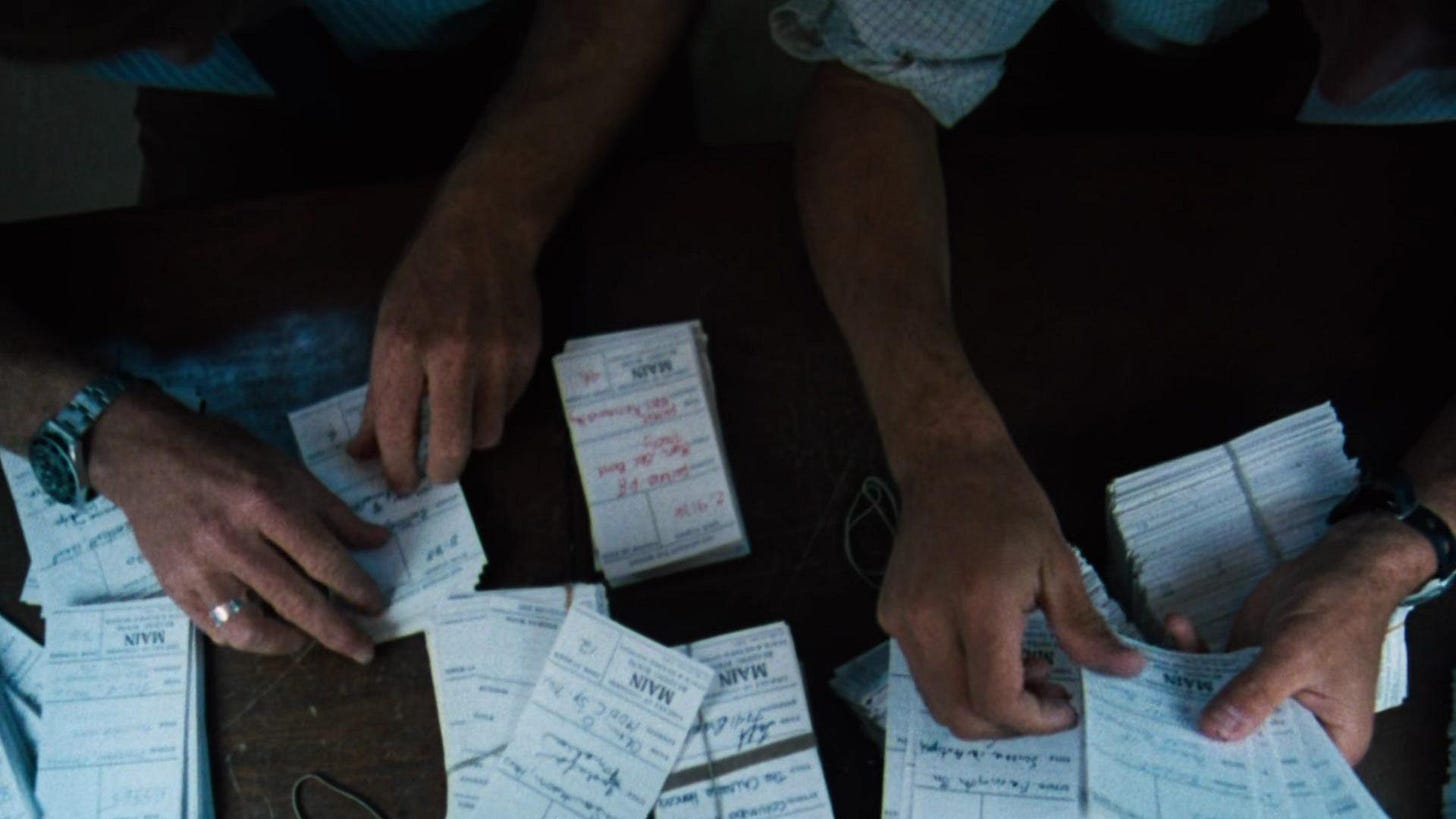

Until George’s forgetfully Uncle Billy (Thomas Mitchell) places the $8,000 (over $100,000 today) that he needs to deposit to keep the Building and Loan afloat in a newspaper, and that newspaper gets handed to Mr. Potter, and Mr. Potter sees the $8000 and he places it in his desk drawer.

When George realizes what Billy has done, he is irate. Screaming at his sobbing Uncle, “Well one of us is going to jail and it’s not going to be me!” Without any other option, George goes to Potter and begs him for the money. And Potter says no.

“You used to be so cocky. You were going to go out and conquer the world. You once called me ‘a warped, frustrated, old man’! What are you but a warped, frustrated young man? A miserable little clerk crawling in here on your hands and knees and begging for help. No securities, no stocks, no bonds, nothin' but a miserable little $500 equity in a life insurance policy. You're worth more dead than alive!” (emphasis added)

The money is in his desk drawer. We the audience know that it is in his desk drawer. He has George’s money. He could give it to him. He should give it to him. It’s not Potter’s. It doesn’t belong to him. But he doesn’t give it to George. Why?

Mr. Potter is evil.

That’s it. He’s evil. True evil. The kind of evil that only exists in storybooks.

The first time I saw this scene, I started sobbing. I was crying so hard that my dad had to stop the movie. I couldn’t have been older than seven. I had never been more upset in my life. Through my tears, I told my dad, “It’s there. It’s in his desk drawer. Why doesn’t he give it to him? It’s right there.” I don’t think my dad knew what to do. I don’t know what I would do if my child had that reaction to a film. It was the first time I understood that people were bad. That people could be evil. That there could be good men like George Bailey and bad things could keep happening to them.

It still makes me upset now. I still don’t understand why Potter doesn’t give George the money. He has the money. It’s in his desk drawer. It’s not his.

I know that people are evil. It still makes me upset.

The backgrounds pulling away like curtains as the dream ballet begins, An American in Paris (Minnelli 1951)

I’ve written extensively about An American in Paris. About what An American in Paris means to me and about what I think it says about art.

But in many ways, it is hard to put into feeling what the film actually means to me. It was one of the first movies that was mine. I understood it in a way that felt special, that others didn’t, it belonged to me and me alone. I arrived at Singin’ in the Rain (Donan and Kelly 1951) (which we will hear about later) late, so for a long time, when I pictured the movie musical – I imagined this one. It was full technicolor, full dance. It was set in Europe. It was romantic, and dreamy, and sad, and everything I adored.

The dream ballet is the most controversial part of the film. It is the part where the film loses most people. It is twenty minutes long, it is self-indulgent both on the part of director Vicente Minnelli and star Gene Kelly, it doesn’t add anything to the plot, whatever whatever, yadda yadda yadda. I don’t care. Who am I to talk about self-indulgence, you’re the one reading an almost 10,000-word piece about my favorite movies. But also, it is none of those things, and even if it was – isn’t that enough? It is beauty and movement for beauty and movement’s sake. It is indulgence because art itself is indulgence. It is magic, beauty, and love, wrapped up in one.

The first time I saw this film, my dad almost turned it off at this point. He had the same criticism as above, except with the added kick that the ballet didn’t interest him. I told him that I wanted to watch it, “We have to see how the movie ends.”

“They get together.”

“But how?”

“They dance.”

“Ok, so let’s watch it.”

He left the movie on but decided to leave the room.

This is what I mean when I say this movie was mine. This part was mine. It was something thrilling that I could discover. I got to see Jerry and Lisa fall in love on my screen and no one else did. Someone else could know the ending, but only I would see it. And the added benefit? I was a ballet dancer. I understood the language of ballet and how the world moved around them. It was thrilling and exciting.

An American in Paris is all about merging the forms of performing arts (ballet, symphonic orchestra, and opera) with the language of film. How do you shoot an opera or a symphony using the techniques of film? What does that look like? Is it still the same thing or is it something new?

Minnelli asks these same questions with the dream ballet. How do you elevate what at that point was a mainstay of Hollywood film? His answer? You just let them dance. You use the things that only film can do – sets, instantaneous costume changes, close-ups – and use them to let people dance.

The dream ballet in An American in Paris begins in earnest when the walls behind Jerry (Gene Kelly) part behind him and reveal a magnificent technicolor soundstage. The sets look like watercolors. An artist’s rendering of Paris. Jerry Mulligan, the wannabe painter, gets to dance through his version of Paris.

It was this moment that I remember thinking “Oh, this is what art is. This is what I do when I dance. I try to do that.” It captured me. I wanted to dance like that for years.

Even now, years after my dancing career has ended and my shoes have been hung up forever, I see the wall part and I want to start dancing again. I want to fall in love and have my heart broken in twenty minutes again. To dance through a city I know, but only in my imagination, and meet a girl I thought I knew, but never really did.

Furiosa realizes that her home is gone, Mad Max: Fury Road (2015)

A change of pace! A non-musical! Wow! Morgan can like those!

Fury Road is one of those movies that changed my life in multiple ways. I remember seeing this movie in my basement because it was nominated for Best Picture (an Action movie, nominated for Best Picture? I couldn’t believe it) and every single scene was a moment of “I didn’t know movies could do that.” As my friend Dean likes to say, we could have just stopped making movies after this one. It is one of those perfect movies that from minute one grabs you and doesn’t let go. It is pure adrenaline and “this is the coolest shit I’ve ever seen in my entire life” for its 120-minute run time.

I think that’s why this moment stands out to me. It’s the one moment the film takes a breath. In reflection, it’s similar to “Feed the Birds” in Mary Poppins. The movie is running without a moment to pause until it does. It forces you to sit up. It stands out.

Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller 2015) is one long chase scene, the cast drives in one direction and then they drive back. It is subtle and plotless, but extremely character-driven. Unlike Miller’s previous Mad Max films, this film isn’t about Max (Tom Hardy) at all. Instead, it is about Furiosa (Charlize Theron)’s quest for vengeance and redemption.

In the wasteland, the Citadel is controlled by the inhuman almost cyborg-like, Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne) who controls water and lords over all the green left in the world. When the film opens we see that Furiosa, off on her usual gas run, has betrayed Joe and taken with her his precious brides – liberating them in an act of revolution and redemption. Furiosa, we see early on, used to be one of Joe’s brides as well, as evidenced by a matching brand on her neck. She has promised these brides that she will take them to where she is from, the mythic Green Place, from where men kidnapped her when she was young. We spend the entire movie trying to get to the Green Place. It is the place where Furiosa, the Brides, and Max will be safe. Furiosa’s great journey is to go home.

When we get there, is when the movie pauses. The reunion with her clan and her sister is heartbreaking, especially with the added context of Furiosa: A Mad Max Story (Miller 2024). When she tells the Mothers that her mother “died on the third day,” it has a little more weight post-Furiosa. This reunion that Furiosa so desperately wanted has been a long time coming. Even just watching Fury Road, you feel it. It is a huge testament to Theron’s performance. She’s unbelievable in this movie.

But the bittersweet reunion is taken out at the knees when it is revealed that the Green Place is gone. The land turned bad, and the Many Mothers had to flee. Furiosa and Co drove by it by accident. The cool bird-like creatures that walk on stilts, one of the many “What the fuck is that? That’s so cool” moments throughout the film, are actually the last creatures that can survive in Furiosa’s home. The wasteland claimed another. She cannot go home anymore.

George Miller lets the moment hang. Furiosa drops to her knees and screams – a silent sound, Miller removes any audio, but he leaves the pain. You feel her anguish and her turmoil. It’s haunting.

This moment made Fury Road for me. It was the final moment of “I didn’t know movies could do that.” As a kid raised on animation and noir, I didn’t know action movies could have emotional weight like this. That they could take a breather like this. Fury Road is the coda to Furiosa’s story, as the last scene of Furiosa tells us, but what a coda it is. Both films are masterpieces of filmmaking and mythological storytelling. It is impossible not to rejoice and feel Furiosa’s anger with her when she finally gets her revenge. You have to find your destiny on Fury Road. You are awaited in Valhalla.

Seb Lifts Mia’s Hand as the two begin to dance in the planetarium – La La Land (Chazelle 2016)

Much like the Safety Last! moment in Hugo, this moment in La La Land was one of those “I get it, I got that reference!” moments for me.

La La Land is, of course, a love letter to the Hollywood musical, and there is no film it is more indebted to than An American in Paris. It ends in the exact same way – with a dream montage where the two leads get together and live happily ever after. This dance sequence in Griffith’s Observatory is the first homage to An American in Paris that I remember seeing and understanding. It was a moment when I felt so smart and so in love with a film. As Mia (Emma Stone) and Seb (Ryan Gosling) lift into the sky, I felt the same feeling I did when watching Cinderella – “So this is love.” And as I realized it was a dream, I understood that it was a reference to An American in Paris. And then I understood what that allusion meant. Mia and Seb wouldn’t end up together, just like Jerry and Lisa. But they could dance together for a while. I bought the fantasy. I was just as upset as I was supposed to be when they broke up. Even though I knew it wasn’t meant to be, the fantasy of the Hollywood romance was good enough.

“Mr. Graysmith, I drew all of those posters.” – Zodiac (Fincher 2007)

There’s something very special about a budding cinephile and the indie auteur film they saw at an impressionable age. Everyone has one of those movies, this whole list is essentially those movies. But there’s something so exciting about a movie that changes not just the way you think about movies, but the way you think in general. David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), which I watched on my cell phone, splitting an earbud with my little sister, on a train in Italy, was that movie for me.

Zodiac is not really a horror film, but it is still the scariest movie I have ever seen. There is something eerie about Fincher’s meticulous recreations. They are overly realistic. The sounds of the knives going into the victims’ bodies sound like a butcher carving an animal– clean, and surgical. It makes it more visceral. But a good horror movie is not enough to make me lean in, to make it one of those moments.

No, it is the slowness of Zodiac that becomes scary. It is a procedural -- painstakingly scripted based on the real detective’s case files. Fincher relies on a slow build of time to create tension and terror. He is using the Hitchcock adage of showing a bomb under the table with a timer and then showing the normal scene occurring at the table. Except the bomb is a serial killer and the timer reads forty years. You know that the bomb could go off at any moment, it is just a matter of when. You know the Zodiac could kill at any moment. It is just a matter of when.

This line, “Mr. Graysmith, I drew all of those posters,” delivered with pure brilliance and restraint by Charles Fleischer, is the exact string pluck of tension. Everything suddenly seizes up. We’re looking at the bomb again. Robert Graysmith (Jake Gyllenhaal) is alone, searching for a handwriting match for the Zodiac and this man slowly reveals that the handwriting that Graysmith is looking for is his. And all of a sudden you remember that there aren't a lot of houses with basements in Vallejo County, and Detective Dave Toschi (Mark Ruffalo) thought that the Zodiac needed to have a basement and Graysmith is stuck in this house with a basement, with a man who has the exact handwriting match as the Zodiac.

I have never been more scared in my life. I have never stopped thinking about this movie.

It doesn’t get scarier than that.

The Bird’s Eye Shot of Woodward and Bernstein Going Through the Card Catalogue, All the President’s Men (Pakula 1976)

This moment is a little different from the previous ones. As discussed, cinephilia is a perverse love of the movies. It is what sets apart the movie enjoyers from the movie lovers. Sometimes the cinephile is unable to articulate why they love something. Sometimes they can’t say what it is about the movies that they love. It is innate. Sometimes they don’t even realize that the way they treat movies and the ritual of the movies is different until someone points it out to them.

That is what happened to me. You will notice a lot of these movies are films I came to when I was young, pre-high school. When you’re a kid, everyone loves the movies. We all enjoy going to the movies, getting popcorn, and then leaving. So it wasn’t until high school that I realized that my relationships with the movies were a little different. I knew I thought about them a little differently, as my relationship with Hugo demonstrated, but I always thought that most people loved the movies like I did. I often say that the language of cinema was a first language I didn’t know I could speak – or that I didn’t even need to learn. I just got them. I knew how to speak about them, I knew how they were constructed, and I knew what they felt like. It was intrinsic. I just didn’t realize it was a language not a lot of other people spoke too.

All the President’s Men (Pakula 1976) is one of my favorite movies. It is currently in my Letterboxd top four. It has been one of my favorite movies since I was fifteen. The things I love about All the President’s Men are the things I love about Zodiac – its slowness, its methodical nature, and its hazy 1970s metropolitan setting. Both are like a mystery novel.

Nothing really happens in All the President’s Men. It’s all about Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) trying to prove that maybe, just maybe, Richard Nixon was aware of the break-in at the DNC headquarters in the Watergate Hotel. They aren’t even trying to prove that he was behind the break-in. They just want to know that he knew it was going to happen. I think they spend close to an hour of the runtime trying to find someone who will go on the record to be a second confirmation for a tertiary source. It is mechanical. It is authentic to real journalism. It is incredibly gripping!

I have tried to show this movie to lots of people over the years. I showed it to a high school friend once and I paused it on this shot in the Library of Congress. It is a bird’s eye shot of Woodward and Bernstein flipping through checkout records in the card catalog to find anything related to Senator Ted Kennedy. The camera slowly moves out as we watch other people move in and out of the reading room and the two journalists stay stationary. It is a perfect image of the redundancy and the crusading spirit of the job and of the task. It encapsulates the whole movie to me.

I paused it on this shot to gauge my friend’s reaction which was… nothing. The shot didn’t register with her the way it did with me. She looked at me to try to figure out why I’d stopped the movie and what was so compelling and for once, I didn’t have the words. I couldn’t explain why this shot mattered so much. So, I let the movie play. At that moment I realized that my friend didn’t speak the language of cinema like I did. I loved movies in a different way.

For a long time, I thought it was the wrong way.

Years later, that same friend was living in Washington D.C., and she took me to the Library of Congress to see the reading room.

“It’s the room from that scene in All the President’s Men!”

“Yeah, or the Library of Congress.”

“No, it’s the scene from All the President’s Men.”

“Ok, it can be that too.”

It was the highlight of that trip.

Neo backbends to dodge the bullets, The Matrix (The Wachowskis 1999)

Ok! Ok! I know this is cliché! This is another one of those “we could have just stopped after this one” moments. But it is all about perspective and setting (and a really good movie).

The Matrix harkens back to Susan Sontag’s original adage about film “kidnapping” you. The Matrix is incredibly good at establishing its world, subverting it, and then keeping you there for the entirety of the runtime. As soon as Neo takes the pill, you are hooked for the rest of the movie. This element of kidnapping is what makes this moment so effective. We’ve seen Neo do so many crazy stunts with the matrix. We have watched him gain control over himself and the agents. As he continues to “level up,” feats like this shouldn’t register the way that they do. Each one should feel redundant or like there are no stakes. But directors Lana and Lily Wachowski have succeeded so well at kidnapping the audience, that anything they throw on screen will feel euphoric. Even though Neo is not the prophesized One, watching him gain control, gives us the idea that he might be. The stake is not, “will he beat Agent Smith?” it is “can he prove himself worthy?” This is his Arthurian-sword-in-the-stone-moment. He is the One.

It has been mimicked over and over again. It has reached the point of passé and yet it is still the coolest thing I’ve ever seen on film. If going to the movies is like a religious experience, this is a revelation. This is a message from filmmaking God. Movies can do this now. What’s next?

The feathers flying off of Ginger Rogers’s dress as she dances “Cheek to Cheek,” Top Hat (Sandrich 1935)

I can’t provide a still for this one. If you watch this scene on YouTube or the film on VOD, I don’t think you’ll be able to catch this. The first time I saw Top Hat (Sandrich 1935) was in a movie theatre, projected for a class about the Hollywood musical.

As we know, to the cinephile, there is something different about being in a movie theatre. The theatre makes the whole thing different. More alive and real. Everything is more glamourous and more heightened. The sound is clearer, there aren’t any distractions, and of course the picture is bigger.

I could probably make a separate list about my favorite dance sequences in film, and I’ve already written about a handful of them here. If I did, “Cheek to Cheek” from Top Hat would be number one. There’s an adage in musical theatre that you talk until you feel so much that you have to sing, and you sing until you feel so much that you have to dance. You talk, sing, dance, until the final curtain drops. That progression is what happens here. Jerry Travers (Fred Astaire) and Dale Treamont (Ginger Rogers) begin talking and are so infatuated (despite Dale’s protests) that Jerry has to start singing. He wins her over and the pair starts to dance. “Dance with me” he sings. “I want my arms around you/the charm about you/will carry me through/to heaven.” The orchestra swells and the pair are off.

Nobody. Nobody. Ever on celluloid. Danced the way Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers did. In the words of my professor who showed me this film, “movies were created so that Fred and Ginger could dance.” They move together with such ease and heavy emotion; every time you look at them, you think this is what true love looks like. This moment. The way he looks at her. The way she looks at him.

I could cite that orchestra swell as the moment. It doesn’t exist on any recorded versions of “Cheek to Cheek” and it sounds unbelievable in a movie theatre. But instead, it’s something smaller, something easy to miss.

The dress that Ginger Rogers is wearing is covered in feathers and as she moves you can see the feathers fall off of her dress. I felt like a kid witnessing a magic trick. “Did you see that?” I wanted to whisper. “The feathers are flying off her dress.”

I showed this movie to a girlfriend once and tried to point out the feathers, breathlessly, like it was a secret we were sharing. The VOD version I had rented wasn’t good enough. She couldn’t see the feathers.

Last Christmas, Swing Time aired on Turner Classic Movies. Before the film, host Ben Mankowitz mentioned that during the “Cheek to Cheek” sequence, eagle-eyed viewers can see the feathers fly off of Ginger’s dress. That time, I saw the feathers. Movie magic restored.

“Top Hat”, despite being on VOD, is really hard to find. There aren’t DVDs or Blu-Rays available anymore, so you can only catch it on TV, or through your library if you are lucky. While writing this, however, I found out it’s available in pretty good condition on the Internet Archive. So, I’ve linked it here. It’s worth watching. See if you can find the feathers.

“Moses Supposes His Toes Are Roses”, Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donan 1951)

Another entry in the movie musical canon. Even though I adore An American in Paris, I can’t help but love Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donan 1951) too. I’m only human. To contrast this film with An American in Paris (which is a somewhat futile task), the longing and bittersweet joy of the former, is replaced with pure zeal and delight in the latter. I find Singin’ in the Rain to be a complete joy. It is the definition of a comfort movie. Every musical sequence is better than the last; each one is stuck in the canon and the firmament of American cinema, and yet it feels new every time.

“Moses Supposes” where Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and Cosmo Brown (Donald O‘Connor) turn the diction exercises Don has been assigned onto its head by tap dancing all over the speech coach, is the best showcase for Kelly and O’Connor’s talent and also the gayest scene in the movie. The latter part isn’t super important but worth noting for my purposes at least. It’s a romantic duet, as much as the actual romantic duets in the film are. It is also filled with so much high-energy dance, cheeky wordplay, and sheer fun. The line “Moses supposes his toes are roses said Moses, supposedly.” Is my favorite of the bunch, which is why it gets the mention here. Nothing has ever made me feel like what I felt when I first watched this scene. I have to keep rewatching the movie.

The first time I saw Singin’ in the Rain I went home and found the “Moses Supposes” scene on YouTube because I needed to see it again, it was that gripping. I started crying laughing when I saw this comment that read “I’m so glad I finally remembered some of the lyrics to this song, because googling ‘two gay men taunt a speech therapist with tap-dancing’ wasn't getting me anywhere.” I think about it every time I see this movie. “Two gay men taunt a speech therapist with tap-dancing.” Yeah. That’s what’s going on.

Alicia kisses Delvin and brings up her left hand, placing the wedding ring in the center frame, Notorious (Hitchcock 1946)

We’ve arrived at the end of the list. In my recent-ish spring wrap-up, I wrote about my first time watching Notorious, and I stand by everything I said there. This is my favorite Alfred Hitchcock film (even after rewatching Rear Window (1954) earlier this summer). The tension is perfect, the romance is perfect, and the performances are perfect.

Hitchcock’s camera work really shines in this movie and in this scene specifically. It’s so masterful that the Criterion edition of this film features a documentary just on the cinematography. His actors are blocked so well, especially Ingrid Bergman, who plays the unwilling naïve spy, Alicia, who falls in love with her handler, T.R. Delvin (Cary Grant). Delvin has tasked Alicia with marrying a former Nazi spy, in the hope that they can find out further information about the work he is still doing for the Nazi party. Everything continues to get muddled as Alicia falls for Delvin, Delvin becomes infatuated with her, and her Nazi husband begins to suspect them both. Delvin finally realizes the error of his ways and what he made Alicia do once her husband poisoned her and he comes to save her, finally confessing his feelings.

Maybe it’s bad form to quote myself in this but the best explanation of why this moment was the one that stuck it's claws into me is the text I sent my group chat:

guys….i CANNOT find a screencap

but there is a shot in this movie of ingrid bergaman and cary grant kissing (but the hitchcock breathing close to each other hayes code way), and her right hand is grabbing his face. he grabs her head to pull her closer and she reaches up with her LEFT to cup his face and her wedding ring is center frame….OH THATS CINEMA”

It is the culmination of everything they’ve sacrificed to get there, everything they mean to each other, and everything that is still at stake. In short, it’s why you go to the movies.

There you have it, the cinematic canon, as defined by me. I hope you enjoyed. Please feel free to share your cinematic canon and those moments in the comments. I’d love to know.

Watch more movies, go see more movies. Let them kidnap you.

This was a fascinating read! I’m definitely not a cinephile (not sure I even knew it was a word), but as I was reading this, I did have two moments from my favorite movie, The Matrix, come to mind. So when I got to one of them in your essay, I definitely yelped a little whoop-whoop (if only in my head).

Thank you for at least making me think about occasionally watching an old (pre-80s) movie.